Amid the bare walls of the Convent of San Buenaventura in Betancuria, we meet heritage restoration expert and cultural heritage conservator Loren Mateo Castañeyra. From there, we make a leap into modern Fuerteventura to explore the remnants of the old Puerto de Cabras, where the surviving ledge holds “the living memory” of the majorera capital.

Under the ruins of the century-old Franciscan convent, Mateo Castañeyra reflects on how in Betancuria “another new culture is born” with the arrival of the Franciscans and colonisation from the early 15th century. He advocates for the austere beauty of majorera heritage, a cultural nakedness synchronised with the island’s landscape:

“Fuerteventura is rich in many ways. In landscapes, churches, hermitages, and archaeology, which is just beginning to be uncovered. Perhaps, it has been regarded from other islands as a poor island. But it is very rich in many cultural elements. The archaeological heritage holds a wealth that we do not yet fully understand,” remarks the expert.

Paradoxically, as he discusses in the fifth episode of Mares de jable, on an island perceived as poor, it was precisely Fuerteventura’s scarcity that curtailed alterations to the heritage we would now regret. The expert refutes this perception, suggesting that those who “absolutely despised it” are now being recognised by historians for the ancient paintings in Fuerteventura. “There is a fantastic collection of paintings, sculptures, altarpieces, and pulpits. The wealth is immense.”

At one point, following the Second Vatican Council, “the liturgy changed, many things inside churches changed. For instance, altar tables were removed, pulpits were eliminated,” he continues. “And because there was no money here to make those changes, it remained, and that has come down to us. For example, in Fuerteventura, we have many more pulpits and altarpieces than in Lanzarote, because there was more money there and they changed them. The flooring of the churches, which here is made of stone and original, has also been preserved.”

“In the face of the simplicity, the whiteness of the hermitages, which had nothing outside—just white—, the colourful contrast inside is astonishing,” although “nowadays we do not see it so much, as many of the mural paintings have been lost.”

This richness even preserves motifs from exchanges with Central America: “In the altarpiece of Santa María de Betancuria, in the attic area, a cacao fruit is depicted, and cacao has never been grown here.” He adds: “The image of the cacao seed, its colours, offers a striking and beautiful contrast against the simplicity and whiteness of the hermitages; from the outside, they had nothing—just white, and nothing else.”

“Previously, all the hermitages and churches were decorated with mural paintings. Imagine walking through the dusty countryside, and then suddenly entering this artificial garden they had created with paint. It must have created a tremendous impact.”

The Poverty Appreciated by Unamuno

“Often, poverty preserves some things that wealth does not, and from that, Unamuno has a sonnet. When Fuerteventura was the arse end of the world, Unamuno was the first to find beauty in Fuerteventura, the first to even claim that poverty.” In the conversation, he recounts an episode from the Basque thinker’s visit to the Canary Islands, when he was invited to the Floral Games in Las Palmas in 1910. “At the floral games, young ladies dressed in long gowns, poets entered…” and “his host did not understand Unamuno’s character. This entirely repulsed him. He then delivered a speech to the young ladies and everyone present.”

“I have become accustomed to attending parties of this nature, which I tolerate, but only because they allow me to speak. I am, however, hostile to them, and I accept them because they are a pretext for discussion. … I dislike these parties because they profane the most sacred thing in humanity, the word, in its noblest form, which is poetry.”

– Miguel de Unamuno, at the Teatro Pérez Galdós, 1910.

In another of his articles, the conservator notes that Don Miguel states, “Fuerteventura is an island for hermits and thinkers, unlike Las Palmas or Tenerife, which are artificial gardens for tourists.”

There Are Restorations Worse Than the Passage of Time

“When a restorer of movable or immovable goods takes a creative approach, doing things he does not know how they were, or using materials that should not be employed, it is an absolute barbarity.” Loren Mateo warns that “often, the intervention is a bigger problem than the passing of time”, and calls on administrations not to restrict their restoration policies solely to protected heritage: “They should set an example.”

He recalls that, given that some goods are not declared of Cultural Interest by the Heritage Law and do not have any level of protection, “there are other items that lack that recognition but are equally interesting, like popular houses. Therefore, even if the law is not explicit in this case, they should be restored in the same manner.” “It has always seemed to me that the best compliment a restorer can receive regarding a piece he has worked on is that it looks as though it has not been restored.”

The Franciscan Cord: Austerity in Landscape and Materials

For Loren Mateo, the island landscape and its heritage maintain a conceptual relationship, as “the philosophy of the Franciscans—of humility, poverty, and austerity—fits perfectly with the landscape of Fuerteventura.” He perceives a “Franciscan cord,” with around thirty hermitages “on the hills, on the mountains, traversing the landscape of Fuerteventura.”

He advocates for minimal intervention, respecting the authors’ style and the original materials provided by the majorera territory: “Most constructions are made from stone and with mortar often simply made from clay,” as well as the whitewashing “with products from the land, lime, and sand.” Hence, his criteria for intervention, in which “the paint consisted of lime, all elements that must be used in proper restoration, not the cements that deteriorate old buildings.”

The Puerto de Cabras District: A Proposal for the Future

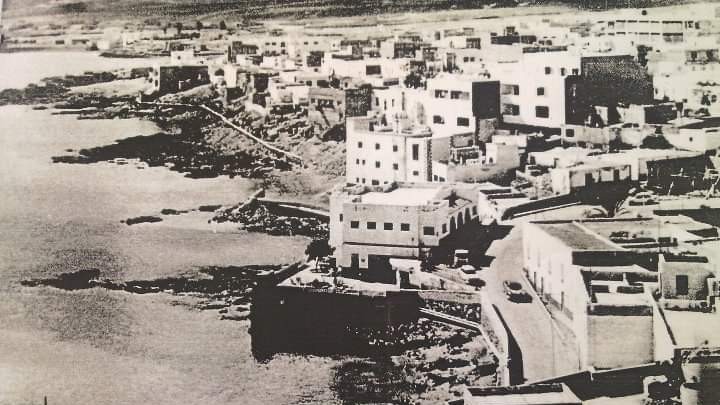

The interview with the conservator concludes along the seaside of the capital. In the area known as Las Escuevas, where cars now pass, is where “the children learned to swim,” as the old Puerto de Cabras directly faced the sea from “this section of the ledge, which is essential to preserve.” “It is the only remnant we have of Puerto de Cabras, the natural entry point to the island from the sea.”

In Puerto del Rosario, the absence of an old town comparable to other Canary capitals opens a discussion about a heritage we have not preserved “due to lack of pride.” “Perhaps the churches were preserved because they were larger, more imposing. But this is a mistake, because even humble houses hold the same value, or more.” “We must bear in mind: the fact that it is a humble house does not diminish its significance. It is immensely valuable, as it is not just a house, but a collective that provides us with an image of what it might have been.”

Loren Mateo revives a historical perspective as he describes the coastline: “it has the face of an old sea wolf, with houses stretching out to gaze upon the waves.” From this, he proposes a symbolic action: although the majorera capital is now called Puerto del Rosario, the name Puerto de Cabras “should be reclaimed in some way (…), perhaps creating a community, the central neighbourhood, and naming it Puerto de Cabras, as a reminder.”

So what can we do to avoid repeating the same mistakes? His stance is clear: “Make it known. Because what is not known is neither valued nor cherished. It needs to be highlighted, illuminated, and shown to people.” Despite urban interests threatening to demolish the ledge to erect a building of up to five storeys, he insists, “I am optimistic. The ledge is not going to be torn down, and we cannot allow it to be.” “I believe that no one with common sense would want this to be lost.”