Two Years After the Coup: Niger Faces a Migration Crisis in the Heart of Its Desert

The Humanitarian Crisis in Agadez

More than 2,000 refugees and asylum seekers are currently trapped in the humanitarian centre of Agadez, Niger. In one of the world’s poorest countries, where temperatures frequently exceed 40 degrees Celsius, these individuals have been peacefully protesting for 340 days, claiming they live in undignified conditions and demanding the right to leave the centre. Last week’s protests resulted in several individuals being imprisoned, with no updates on their status. “We do not feel safe here,” laments Halil, a Sudanese asylum seeker, who has been given a pseudonym for safety.

The Agadez reception centre, housing over two thousand individuals according to UNHCR figures—35% of whom are children and 31% women and girls—has become a stark representation of the effects of border externalisation. Thousands fleeing their countries are awaiting the chance to continue their journey, surviving in a harsh environment where basic necessities are reportedly being cut. Residents have long complained about the lack of medical care, education, and now food. The organisation Refugees in Niger has been raising awareness of this situation on social media, asserting that “Agadez is not a safe place for refugees.” Daily, they gather outside the centre, displaying signs indicating the number of days they have been protesting. The week prior, security forces intervened, leading to the imprisonment of six residents, prompting UN rapporteur Mary Lawlor to call for their immediate release via her profile on X.

Escalating Protests

The protests date back to September 2024, but have intensified in recent months following the cancellation of food services. Halil indicates that he must borrow money from local traders to eat, promising to pay them back later. “A few days ago, I asked a small trader for a loan. He told me no until I settled my debts. Now, I am considering leaving, like many others, due to the difficulties we face,” he confesses. In response to inquiries, UNHCR spokesperson Eujin Byun acknowledges the “difficulties” faced by the centre, which has been “the scene of protests from some refugees and asylum seekers expressing their frustration over living conditions and their prolonged stay at the Centre,” Byun details. As for the food service cuts, the agency states this is part of a long-term plan to promote self-sufficiency, which has been expedited by current funding cuts. Byun clarifies that food assistance will not impact the most vulnerable refugees and applicants.

This centre houses a significant number of Sudanese who have fled their country due to conflict and subsequent civil war. Many have been stranded in this region for years. Halil, 29, was a business administration student at the University of Kordofan until 2019. After fleeing Sudan due to the war, he went to Libya, where he reports having “suffered greatly due to the torture in prisons.” He recounts that upon entering Algeria to reach Morocco, he was intercepted by Algerian authorities, who abandoned him at the Niger border. He claims to have applied for international protection but has yet to receive his refugee documentation, having waited for a year at this centre. “I had an interview for the document about four months ago, and it still hasn’t arrived. Some here have been without documentation for seven or five years,” he states.

Healthcare and Education Concerns

Refugees and asylum seekers also complain about the lack of access to education and healthcare. Halil states there are no doctors at the centre and that they must walk several kilometres to reach a medical facility. “If you fall ill at night, you will die because we cannot go out at night,” he insists. In this regard, the agency points out that the health centre is located 7 kilometres from the humanitarian resource, and that severe cases are transferred by ambulance to the Agadez general hospital. “A primary school established by UNHCR, located within walking distance (700 metres) from the humanitarian centre, is operational,” adds Byun.

Time passes, and asylum seekers and refugees grow increasingly desperate in an arid region with little to do. Halil mentions that he does not work, as finding employment in the area is exceedingly difficult and he also does not speak the local language. He reports spending his days trying to raise awareness on social media about the situation in the centre, updating videos and photos primarily on X. “I tell the world until nightfall when I lie awake in bed with nightmares. This continues until dawn,” he narrates. “Our demand is to leave the centre. We never asked for resettlement in a third country. We just want to escape this situation. It is crucial to go to a country that respects my rights as a human being, where I can live in peace,” emphasises Halil.

The Broader Context of Humanitarian Funding Cuts

The situation at the Agadez humanitarian centre highlights the ramifications of global humanitarian funding cuts. UNHCR acknowledges that the centre’s challenges “are part of a funding reduction impacting humanitarian operations worldwide.” When asked whether the cuts imposed by the European Union following the coup have affected the services provided by this agency, it was noted that “while EU contributions remain important, the overall reduction of funding from multiple sources has affected UNHCR’s ability to maintain the same level of assistance.”

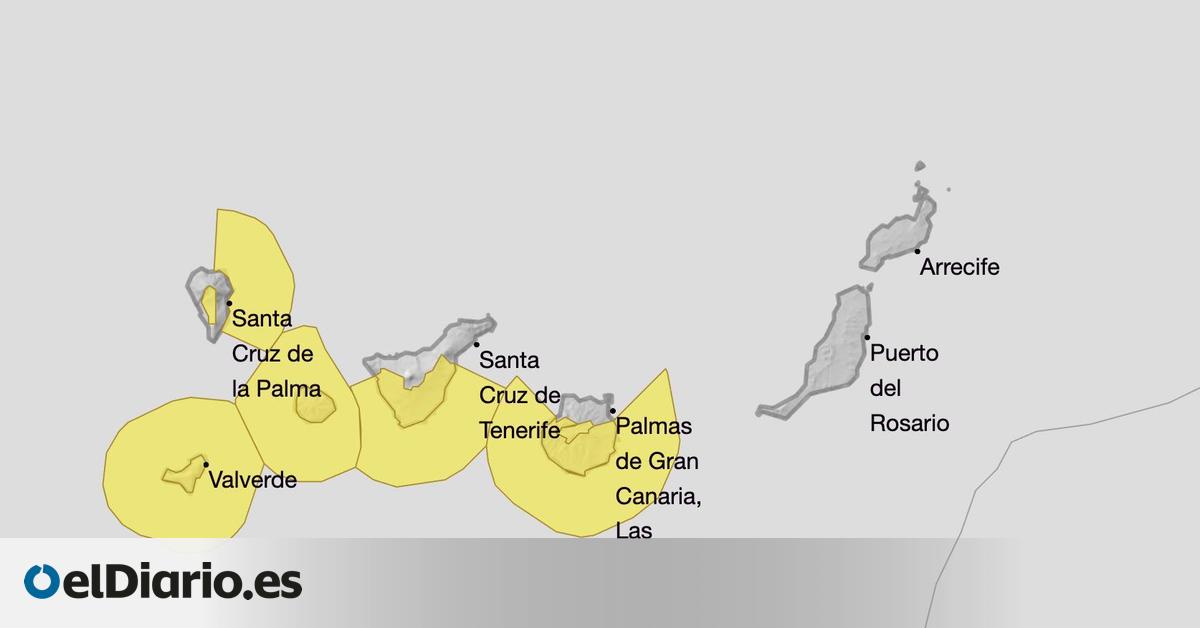

Since the military junta that overthrew President Mohamed Bazoum came to power, several international actors who do not recognise the new government have hastily announced funding cuts for Niger. Both the EU and the United States communicated that various funds would be frozen. Among these funding lines was the NDICI – Global Europe, an instrument of the European Commission designed to assist the most needy countries. According to Dagauh Komenan, a historian specialising in International Relations at the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria (ULPGC), this cutting policy is key to understanding the situation that migrants and refugees face in the country. “Niger is one of the poorest countries in the world and also must deal with jihadist insurrection. The capacity to accommodate individuals returned from Algeria with its resources is quite complicated. It almost entirely depended on European cooperation.”

The specialist elaborates that this scenario is further exacerbated by the EU’s premise that cooperation funds are tied to a country’s willingness to block the flow of migrants. “Since the Cotonou Agreement in 2010 and the one from Samoa, cooperation has been focused on either accepting or contributing to blocking migratory flows to Europe. All those funds have been blocked since the coup. The country is doing its best with its new allies,” he notes.

Niger’s New Alliances

Niger’s new allies are primarily Russia and China. Russian cooperation is focused on military training; “unlike Mali, and contrary to many expectations, Niger has not entirely fallen into the arms of Africa Corps, formerly Wagner.” Meanwhile, Niger’s main trading partner is China, a country that has seen “an avenue open up with the exit of all Western partners,” particularly interested in uranium, as highlighted by the historian. However, two years after the change of government, he notes that citizens have not experienced significant changes: “Apart from a bit of national pride, their wallets are not any fuller,” he concludes.