Fifty years after the dictator’s death, we remember the trail of terror left on the islands for decades

The Francoist repression in the Canary Islands was not the result of direct armed conflict, but rather a deliberate policy of domination. The regime employed tactics of physical, psychological, and symbolic violence to crush any form of resistance. Unlawful detentions, extrajudicial executions, and makeshift detention centres (such as La Isleta, the Lazareto de Gando, and the Fyffes prison in Tenerife) are part of this systematic strategy.

Fyffes prison in Tenerife was a detention centre that came to house over 1,500 individuals in inhumane conditions. Over 4,000 prisoners passed through this facility in twelve years, many of whom disappeared.

Mass graves and ‘sacas’ to the sea

In Tenerife, going missing at sea was a common fate. Victims were taken from their homes or detained at Fyffes, transported on prison ships, and thrown into the ocean, regarded by many as a “great mass grave.”

Numerous investigations document these events; for example, remains showing signs of execution (skulls with bullet impacts) were found in Llano de las Brujas and Tenoya (Arucas, Gran Canaria) during research carried out in 2008 and 2017.

A study conducted in Tenerife by the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory identified 182 fatalities due to Francoist repression (ranging from extrajudicial executions to torture or summary trials), predominantly young men connected to labour parties and trade union organisations such as the CNT, PSOE, or Communist Party.

Some sources estimate the existence of at least 21 documented mass graves throughout the archipelago (in Tenerife, Gran Canaria, La Palma, and La Gomera) with 471 reported disappearances: 337 in Gran Canaria, 49 in Tenerife, 74 in La Palma, and 17 in La Gomera; in addition, 122 executed individuals have been identified.

The repression in Fuerteventura

In Fuerteventura, there were documented arrests, summary trials, and some executions (at least two individuals from Fuerteventura were executed, although in Gran Canaria). Officials, teachers, or those with a “suspicious” profile were purged, and many were transported to the island as a form of punishment or confinement. The case of the republican teacher and intellectual Juan Millares Carló, father of the painter Manolo Millares, exemplifies this logic of exile within the archipelago.

Subsequently, Fuerteventura was used as a site of exile for political opponents. A notable case is the “Contubernio de Múnich” (1962): several Christian Democrat politicians were confined in Fuerteventura for months after participating in opposition meetings in Germany.

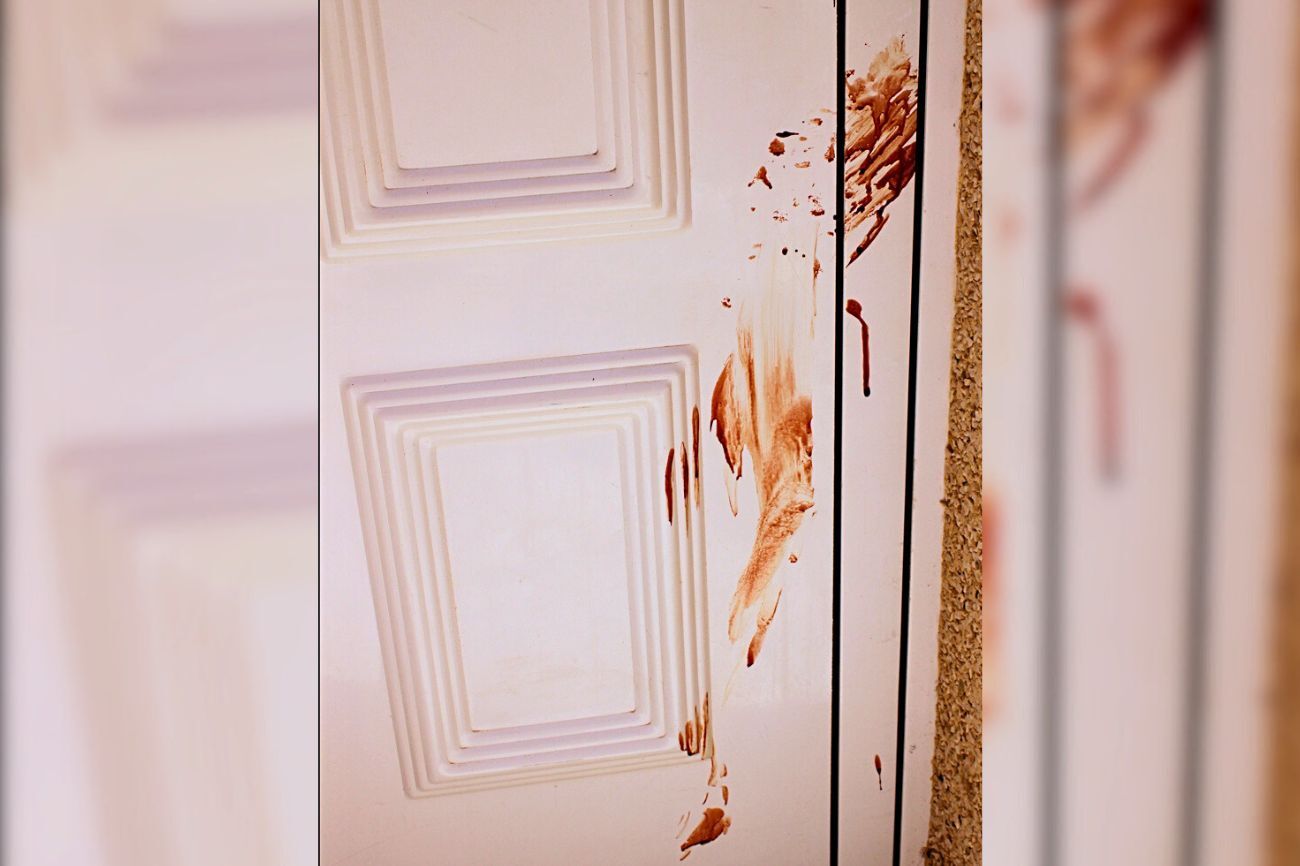

Between 1954 and 1966, the well-known Agricultural Penal Colony of Tefía operated in Fuerteventura, a “re-education” camp resembling a concentration camp. Although its creation was officially justified by the implementation of the Vagrants and Idlers Law, in practice it was used by the Francoist regime as a tool for social and moral repression.

There, those deemed “socially dangerous” were interned, including common criminals, political dissidents, homosexuals, and trans individuals. Inmates endured forced agricultural labour under inhumane conditions, as well as humiliation, sexual repression, and religious indoctrination, a typical strategy of ideological submission characteristic of Francoism.

Institutional initiatives

In 2025, the central government allocated grants for various investigations and exhumations across the islands:

– La Palma: nearly €96,000 for intervention in the grave at Vaguada de la Araña (Fuencaliente).

– Tenerife: approximately €100,000 for studies at Fuente Cañizares, Pozo de los Alemanes (Arona), Cuevas de María Jiménez and San Andrés, as well as coastal areas such as Garachico, Los Silos, and Buenavista del Norte.

– Gran Canaria: €100,000 for interventions in sinkholes, graves, and wells.

– Fuerteventura: €100,000 to museumise the Tefía penitentiary colony as an interpretative centre on LGTBIQ+ repression.

Exhumations: memory and justice

Exhumations of graves are a fundamental tool for activating memory, highlighting the actual scope of repression (spatial, social, emotional), and providing reparations to families. Their execution fosters discussions on trauma and promotes social justice, dignity, and recognition of the victims.

This effort also addresses the necessity for historical justice, in line with recent initiatives throughout Spain. In municipalities such as Campillos (Málaga), mass graves containing remains of republican victims have been documented, including an exceptionally high percentage of women—over 20%, compared to the national average of 3-5%—revealing patterns of extreme violence. Other significant exhumations, such as those in Jaén (graves 548, 438, and 702 with around 1,250 bodies, including prominent figures of republicanism), illustrate the scale and symbolic and human value of these initiatives.

A critical viewpoint on the Francoist “funeral apartheid” is also essential: the regime prioritised tributes to its “fallen,” while relegating republican victims to the anonymity of mass graves.